Kyoto Day 1: Shinkansen Bullet Train, Hotel 9 Hours, Fushimi Inari Taisha

Sunday in Tokyo, the skies were bright blue and the air crisp.

J and I walked through the massive tree lined paths of Yoyogi Park to Meiji Shrine. Lots of colorful offering of produce were arranged on miniature boats that were landlocked within the walls of the main courtyard.

In Harajuku we searched for colorful counter culture, but almost everyone’s dress was both stylish and mundane. Takeshita, the unfortunately named teen shopping street, was a good place for trinket browsing. I almost bought a small stuffed Gizmo from “Gremlins” to hang from my backpack.

Ash tray.

Brick braced.

Careful.

Table weight.

Colorful overpass.

Pathway.

Offering.

Flowers.

And more.

Sake shrine.

Takeshita.

Mirror forward design.

Lunch came from the basement floor of the famous Iseman Department Store in Shinjuku. The whole floor was full of vendors selling all types of pre-prepared food items, many of them arranged into colorful bento boxes. The food was meant for takeout. A large section of the floor was only desserts, beautifully made, packaged, and displayed like jewelry. Truly gorgeous food, but expensive.

We ate on the rooftop garden of the store (generating a lot of packaging trash), grabbed our bags, and took a train to Tokyo Station to catch our ride out of town.

The Shinkansen, also known as the bullet train, is a network of high-speed railway lines in Japan operated by four Japan Railways Group companies. The trains are pervasive, fast, safe, and reliable.

From Tokyo Station the trains to Kyoto came every ten minutes, with punctuality measured in seconds. We bought reserve seats for a hefty $300+ per person, roundtrip.

Inside, a clean spacious cabin provided power outlets, leg room, and a wide aisle to get to vending machines or the bathroom. Much more comfortable than a plane.

The two hour ride offered a 180mph, nauseating view of smaller cities and countryside. We didn’t have a window seat, so we had to watch over our row mate’s shoulder.

One of Japan’s famous “Fast Retarded Dolphin” trains.

A team of ladies in pink would swiftly clean and reset the seats at the stop. They were like a pit crew.

The tray table map.

Lots of room. If only planes were this spacious.

Our hotel was a short subway ride and walk from the main Kyoto Station. Hotel 9 Hours is a capsule hotel, meaning that there are shared bathrooms and small sleeping cubbies rather than private rooms. It’s as close as men get to living as bees. The place was super modern and minimal, like a cross between a hospital and space ship. No honey.

One of the brightly lit shopping streets off Shijo Dori near our capsule hotel.

A steampunk dessert machine that automated the process from deposition to hot iron branding.

The entracne to Hotel 9 Hours.*

The sleeping capsules.*

After searching the bustling pedestrian streets nearby, we settled on a soba restaurant with bilingual menus. Like many of the mall restaurants we had eaten at, this one was surprisingly good.

Back at the hotel, J and I planned our next day in the communal lounge space. After a quick well-wishing, we got in our separate elevators to shower and travel into the far reaches of space.

But I couldn’t sleep. It wasn’t from claustrophobia, but the constant noise of my neighbors snoring, tossing and turning, or climbing out to use the restroom at the end of the hallway. Additionally, the heat was on too high as compensation for the thin blankets.

I emerged from my capsule a wreck, but it was our first day in Kyoto. And not even lack of sleep or cold rain would keep this male man from his planned route.

But first, we had to find and switch to a different hotel.

Due to a combination of tourism and a national holiday, all of the rooms in the city were either booked or overpriced. We settled on the APA Villa Hotel, two block from the main train station. Despite the super cramped room, lack of wifi, and $200 per night cost, it was the best option.

We dropped off our bags to the nervous trainees behind the counter, and walked in the rain to a subway station across the river to take a shrine-ward bound train.

Fushimi Inari Taisha sits at the base of a mountain that includes trails to many smaller shrines.

Since in early Japan Inari was seen as the patron of business, each of the torii (the vermillion gates) is donated by a Japanese business. There are gates of all sizes, from large ones covering the paths, to those placed on tsuka (the smaller shrines).

Shrine estimators estimate that Inari has as many as 32,000 tsuka.

Despite the steady rain, an annoying amount of people were already blocking views of the torii. Everyone was polite about it at least. Luckily, the farther up the path we went, the sparser the people. By the time our shoes were soaked we were only encountering someone every fifteen minutes.

We almost decided to give up too, as I was feeling ill, tired, and both our clothes and camera were getting wet. But the scenery was too good, and even if it meant wiping my lens off every few minutes, I was going to enjoy it.

NIK TIP: When the crowds are bad, never underestimate people’s reluctance to walk up hills in the rain.

Fushima-Inari Station in the drizzle.

Our exciting and necessary purchase.

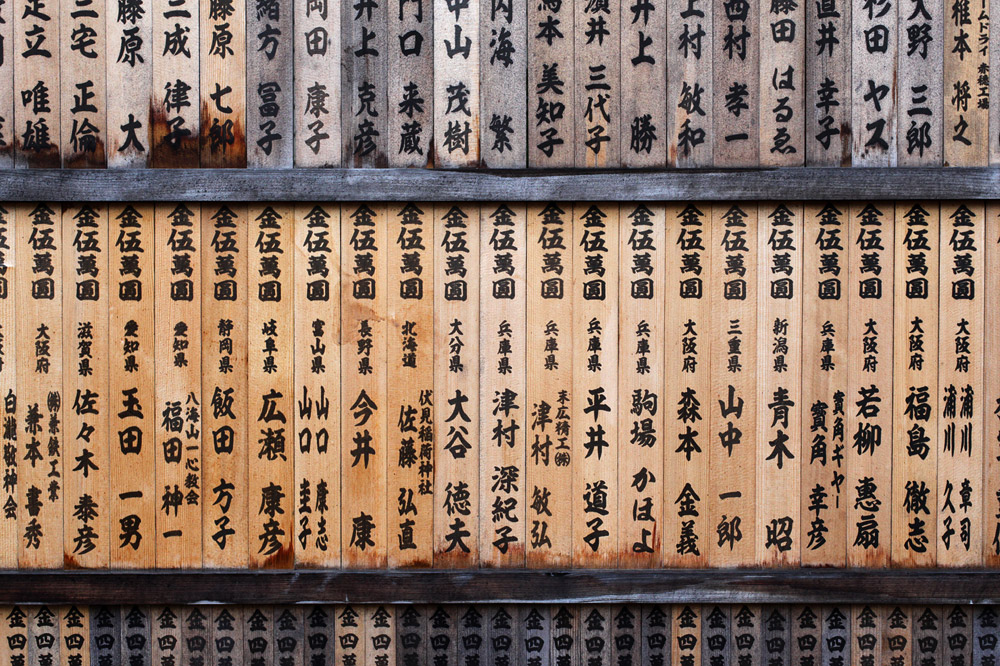

A stacked wall.

A large wall of small prayer sticks leading to the entrace of the grounds.

That’s so Japanese!

One of the numerous fox (kitsune) sculptures watching over the shrine.

Our first taste of the famous vermillion gates of Fushima-Inari Shrine.

Further down the path.

A gateless path.

Outside the colonnade.

High road or low road.

The inscribed side of a torii.

Torii spider.

A stone gate to a more private tsuka shrine.

Waterway, fed by the constant drizzle.

Miniature torii.

Shrinerettes.

The orange ascension.

Tsuka.

Wet feet and maple leaves.

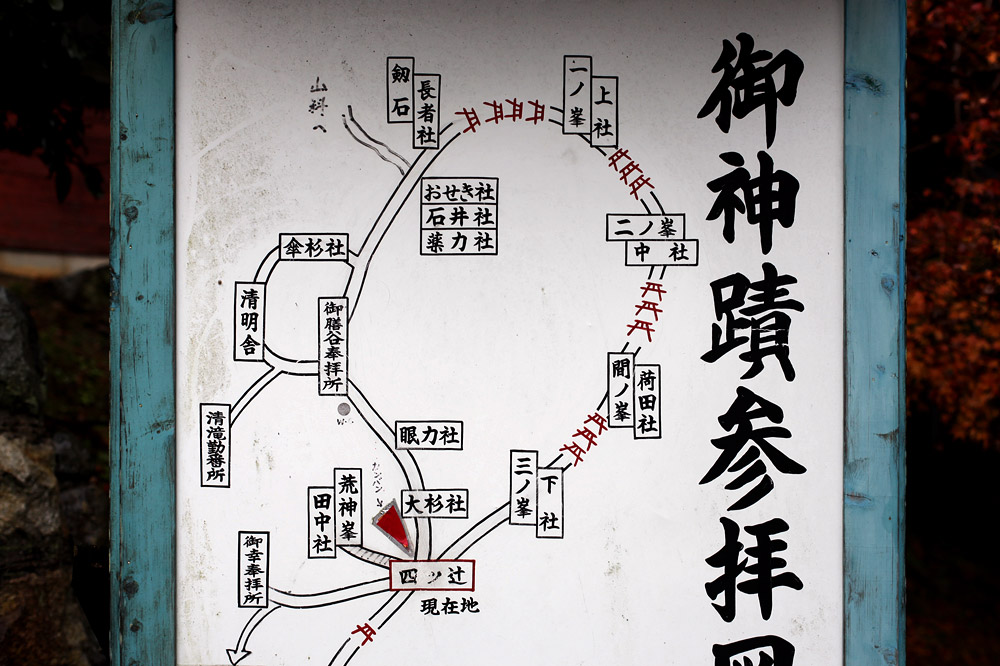

A slightly helpful map near the top of the mountain.

Approaching the top.

Hand washing station.

Leaf-covered stairs make for slippery footing.

The webmaster.

Autumn colors.

Cistern piping.

Entering another shrine area on the backside of the hill.

Leaves frozen in a web.

Another place to wash hands.

Maple leaves in a babbling ditch.

The shrine was moody and magical. The structures didn’t feel old, but the energy of the place did. The less crowded paths allowed a quiet chance to listen to the rain and focus on following the vermillion tunnel from shrine to shrine. We passed through well maintained areas, to sections missing torii. From little village like intersections with tea houses, vending machines, and chances to explore the smaller prayer mounds. The tea houses had given up hope for the day, and their doors were unlocked but closed. Hiding in the dry shadows, a caretaker would watch us pass.

I said goodbye to the fox with a key in its mouth, and we walked back to the Inari train station.

Our lunch spot was no shoes allowed, and my socks were steaming as I ate my also steaming bowl of tempura topped soba.

A meandering walk followed a swiftly flowing canal and river. Along the way, we passed through some dreary looking areas with lots of corrugated metal, and powder blue construction fences.

A dryer view of the station.

And looking north.

Along a canal the scooters drove recklessly.

Classy.

Beautifying the river one concrete block at a time.

The wet side of the tracks.

Convex portrait of a soggy couple.

Kyoto’s temporary fences.

A freshly marked intersection.

It took an hour to get back, and by the afternoon the lack of sleep was bringing me down.

After a dinner of rice-based snacks, I went to bed as emphatically as a wet log falling over in the woods.