Trails and Trestles

No rails, no ties, just gravel and memories.

As a child, I was both terrified and drawn to the train tracks on the hill behind our neighborhood. Some threats were real. The train approached with a short rumbling warning, forcing me to scramble into the underbrush. The occasional drifter/psychopath forced the same response. Stray dogs. Snakes hiding around the railroad ties. The trail to get to the tracks was full of poison ivy, burs, and broken boards with shoe-puncturing rusted nails. The whole area seemed designed to injure me, but I held it in high regard.

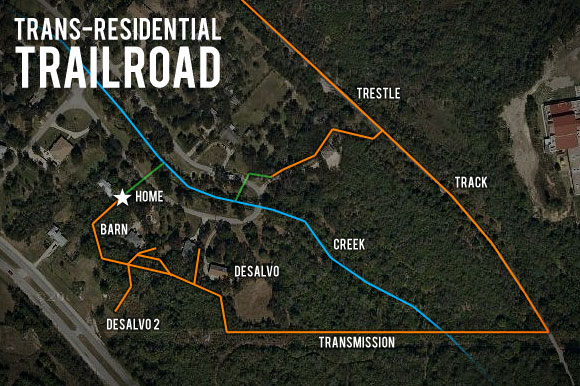

The train tracks were a seldom-used section of trails I made called the Trans-Residential Trailroad. The goal of the trails was two-fold: to be able to travel around most of the neighborhood unseen and to spy on my neighbors. I cut a pathway from my parent’s backyard, up through our old barn, and along a wooded hillside to behind our neighbor’s house. The DeSalvo’s were my main spying interest, in part because they lived closest and I had a crush on their daughter. A variety of smaller trails branched out to different vantage and escape points. Behind the DeSalvo’s, a section a trail passed natural clearings and through a hole I cut in a chain-link fence. Following high voltage transmission lines, it was a straight shot down the hill, into the creek, and up to the train tracks.

The trail network: Orange lines denote trails hidden in woods. Blue is the trail hidden inside the creek bed. Green marks the few sections that weren’t hidden. DESALVO2 marks an Italian restaurant the family owned.

The transmission lines seen from the tracks.

The shell of a Caravan. Oddly enough, we had this same model. How on did it so far down the tracks? Was it used in a robbery? Was it our old van?

Another view.

And another.

I was fanatical about maintaining the trails. Much of my childhood was spent wandering around the woods with shears and a saw. The pruning was so I could escape through the trails without gouging my eyes on a branch. This worst-case scenario only came once, thankfully. And I made it through without a scratch.

Once I found a rifle bullet embedded in a tree, shot from the DeSalvo’s direction. I had trouble not imagining similar bullets splitting my head open. It would be like a scene in the movies where the camera follows the bullet as it plows through the target’s binoculars, eye, and splatters out the back. The eye seems like such a bad place to get shot.

Of all the time I spent out there alone, with our dog, or my friends, I don’t think I ever saw anything worthy of spying. It was more the act of voyeurism that was intriguing. I was so afraid of being caught, that I stayed far from the action.

From the train tracks, it was possible to both stay hidden and see into backyards. It was also the highest point in the entire neighborhood, so it felt like being King. There was a large trestle that I’d throw stones from. I’d count the seconds before hearing the impact and estimate how tall the bridge was. Answer: pretty tall.

Across the trestle.

The aging supports.

Thick, oily, and crumbling wood.

The track was surrounded by woods. A few clearings were used as illegal dumps. They were full of rusted cars, appliances, and garbage. One path led into the grounds of a monastery. I remember a few family hikes when I was younger where we’d spend the whole day discovering the natural wonders and garbage around the train tracks.

Berries.

It seemed like such a long journey to follow the tracks to where they crossed a major road. At this intersection, they passed under an unfinished trestle for an ill-fated interurban rail, then over the road.

The unfinished section of rail.

Another view.

Once from this bridge, three male youth mooned my mother, sister and I while we were driving by.

By middle school, the trains stopped running. The Santa Fe Railroad spur ran between a concrete plant to an aggregate quarry. Now that quarry is home to warehouses, apartments, Walmart, and the various stores and restaurants of suburbia. One of the dumps is now a community center. Another is a low income housing development. The rails and ties are gone and the route is overgrown with trees. All that’s left is the gravel.

It all seems so small now. The drop from the trestle seems shallower, the distance to the road shorter. The size ratio between my current self and the track isn’t much different from my childhood body. But my view of track has shrunk to fit amongst all of the other tracks I’ve traveled. I guess the only thing that seems bigger as you grow up is your gut (and saddle bags, for the ladies).

The track goes over the road, through the woods, and into the future.