Dental Tripping

Note: This post is part of a series of stories about a boy. Find the rest and other writing by browsing the “writing” category. Feel free to drop a comment and let me know if you liked it, or how it can be improved.

Gaylord had a winning smile, no doubt about it. His teeth were full, straight, and solid-looking. For some reason, the boy’s permanent teeth came in early and suddenly. While Gaylord’s classmates were walking around with gap teeth and playing with the others dangling by nerves, Gaylord was well into a his new set. He never had braces, a fact that came as a shock to his childhood dentists.

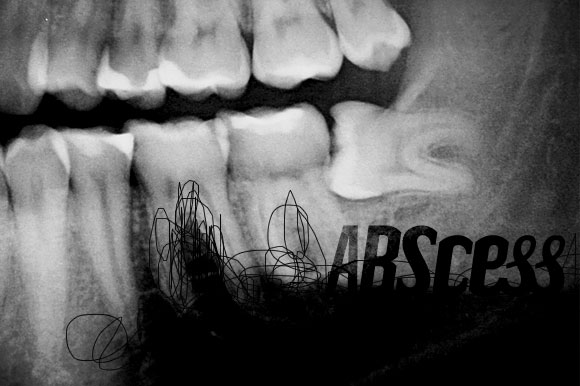

But despite outward appearances, these teeth were a battleground of death, decay, and worry.

Dental hygiene was in casual regard in Gaylord’s house. His father brushed his teeth daily with such vigor that the tooth brush looked like it had been sat on. But over the years, tooth after tooth was pulled from his father’s mouth by an old Hispanic dentist named Dr. Gonzaga. This wasn’t the kind of dentist you went to for preventative care. Dr. Gonzaga was a last restort, and most likely his office was only equipped with various pliers. Thankfully, Gaylord never went to this dentist but he had clear memories of the man’s large greying mustache and forehead mole.

Gaylord’s mother had all her teeth, but some molars needed root canals due to cavities left unfilled. A few of her teeth had died already and were a darker shade. Her front teeth were getting thin at the biting edge, and had cracks running to the gums. Any hard food was bitten at a skewed angle to reduce the contact with these fragile blades. Eventually, his mother got two vibrant white crowns on her front teeth. She was able to bite through pipes, but feared that she looked a little like a rabbit.

Both parents had given up on their teeth, and rather than smiling vicariously through their son, they never really realized that proper dental care would prevent all that they had suffered.

Gaylord had a toothbrush, but he never flossed. The permanent teeth pushed out a mouthful of sorry looking baby teeth that resembled rotten kernels of corn. Soon, bacteria got to work on his new choppers.

The dentist Gaylord went to for most of his childhood worked from a flat building in a very normal looking office park. But inside, all of the dental work was performed in a sloppily build, neon-lit cave. The walls had fish tanks for windows and were stuccoed to look like stone. Doorways, light switches, and informative posters glowed under the purple light. Even without nitrous, the whole thing felt like a Flinstones drug trip.

“You have twelve cavities,” Gaylord’s dentist said without emotion.

Gaylord started crying. His mother, sitting in on a stool nearby started some math calculations and seemed on the verge of crying too.

“We only have money to fix some of them right now,” Gaylord’s mother told the dentist. “Can we schedule to fix the four most important ones first?”

Of course they could.

Gaylord and his mother walked out of the cave in silence. As she scheduled another appointment, Gaylord thumbed through the magazines in the waiting area. For a children’s dentist, the lobby didn’t have many magazines for children.

The light was harsh and the air muggy in the parking lot. The late summer sun had turned their black station wagon into a solar cooker.

Gaylord got the four fillings eventually. But by then, he had new cavities, and some of the old ones had gotten big enough to warrant crowns. In the battle between dental care and dental problems, the problems always seemed a step ahead.

Eventually a laundry list of repairs had been made inside Gaylord’s mouth: 10 fillings, 2 crowns, and a bridge between one baby tooth that was extracted. Somehow, his parents were able to pay for everything. Things seemed to be going fine.

Then came the discounted bag of Valentine’s Day candy.

A few days after Valentine’s day, Gaylord was shopping at the grocery store with his mother. They were clearing out shelves of seasonal merchandise and had slashed prices on all the pastel colored goods. The candy and cards had the deepest discounts and there was a bag of hard sour candies that were practically being given away. Gaylord added them to the cart.

The candy was awesome. A hard, shiny shell coated a chalky and sour center. In a rush to get to the centers, Gaylord ended up chewing rather than sucking most of them. In three days, he had finished that bag of clearance candy. His molars felt tender.

One night Gaylord had a dream. He was in a warehouse talking to a group of people who had just done something to rial a gang. Suddenly, the gang crashed their cars through the wall of the warehouse. The members got out and started beating everyone up. Some people were tied, others were killed. Gaylord was wrapped up in a blanket with only his head sticking out. The leader of the gang came over and looked down at the boy.

“You guys work for us now,” he said with a sly smile. “But first we need to build some trust.”

The man took out a thick stack of laminated papers and stuck them in Gaylord’s mouth, telling him to bite down.

“I want you to guard these documents. We’ll be back for them. Oh, and don’t think about taking them out of your mouth. They’ll explode if you do.”

The gang left. Gaylord was alone in the warehouse, lying on the floor and biting down on the papers. His teeth hurt. He needed to rest his jaw…

A blinding pain woke Gaylord from his troubling dream. At first he thought that the bomb had exploded in his mouth, but it was just a tooth. One of his crowned teeth throbbed and filled his head with shooting pain.

Gaylord kept the pain a secret for a week. Then it was gone.

A while later, the boy was looking at his confusing tooth in the bathroom mirror when he noticed a pimple-like blemish on his gums. Gaylord pressed it with his fingertip. It didn’t hurt. Over the next few weeks the sore grew bigger and bigger. He tried poking it with a thumbtack, but it was surprisingly firm. He showed it to his mother and she arranged a dental visit.

These were the post cave years. Gaylord felt he was too old to be hanging out in a cave, so his family started going to a normal looking dentist office on the far north side of town. His new dentist was very friendly, and his receptionist even more so. The heavily tanned and skeletal woman seemed to care about Gaylord and she remembered all sorts of things he had told her on past visits. Maybe she kept notes like some dentists. If so, she did a good job of acting like she didn’t. The dentist had a mustache like his father’s dentist, but it was more modest. No forehead mole.

“Your tooth is dead. That bump you see is puss from the infection in the root that has spread to your jaw. It’s a pretty big infection.” Gaylord’s new dentist looked at him for confirmation.

Gross.

“You’ll need a root canal. We should be able to keep the crown, but you might need a new one. The first thing we need to do is stop the infection.”

The sore was punctured and drained, and Gaylord was prescribed antibiotics. Since he was still too young to swallow pills, the medicine was suspended in a pink, sweet fluid that tasted delicious. He took his first dose in the parking lot outside the pharmacy.

It was lunch time, so they decided to drive through a fast food place before getting on the highway. Something about the greasy smell in the parking lot put Gaylord’s stomach in knots. He moaned and his mother stopped the car so that he could open the passenger door. Heave ho, vomit across the drive-through. For some reason it seemed to be comprised of canned peaches.

The root canal went smoothly. He was pumped full of novocaine, the crown was removed, and a hole was drilled in the tooth stump down to the dead nerves. Even without sedatives, the whole process was oddly calming. The dentist had to keep reminding Gaylord to stay awake so that he’d keep his mouth open. After the variety of rasps had removed the dead nerves, the hole was brushed with some kind of harsh smelling chemical and packed with paste. The crown was reattached with temporary cement, just in case the dentist had to get back in there for something he missed. Gaylord wondered if dentists ever left each other little notes inside people’s teeth. Would his note say “Keep this kid. Money pit.”

Gaylord didn’t feel like eating for the rest of the day. His mouth was fuzzy and tasted of chemicals.

That weekend, Gaylord was eating a bagel in his room when he bit down on something hard. Thinking it was a rock in his bagel, he pulled the wad of moist bread from his mouth and flung it out the window.

Then he realized his crown was missing.

Beneath his second story bedroom window was a large bush, grass, and fallen leaves. It was winter, so everything was dry. But everything was brown too, making it harder to find a wad of beige bread. Eventually he did. The crown was swaddled in bread and lying amongst the reeds like baby Moses.

Gaylord wondered if Moses had teeth problems too. Did he ever brush his teeth? If so, did he use some kind of flayed stick? Did a pair of birds sit on his shoulder and pick his teeth clean? It seemed like after living 120 years without brushing, you’d have some pretty nasty breath. What did Mrs. Moses think about this?

But maybe with all the important stuff people were doing back then, they didn’t worry much about brushing their teeth. Good for them. Gaylord had no excuse, and this bugged him Biblically.